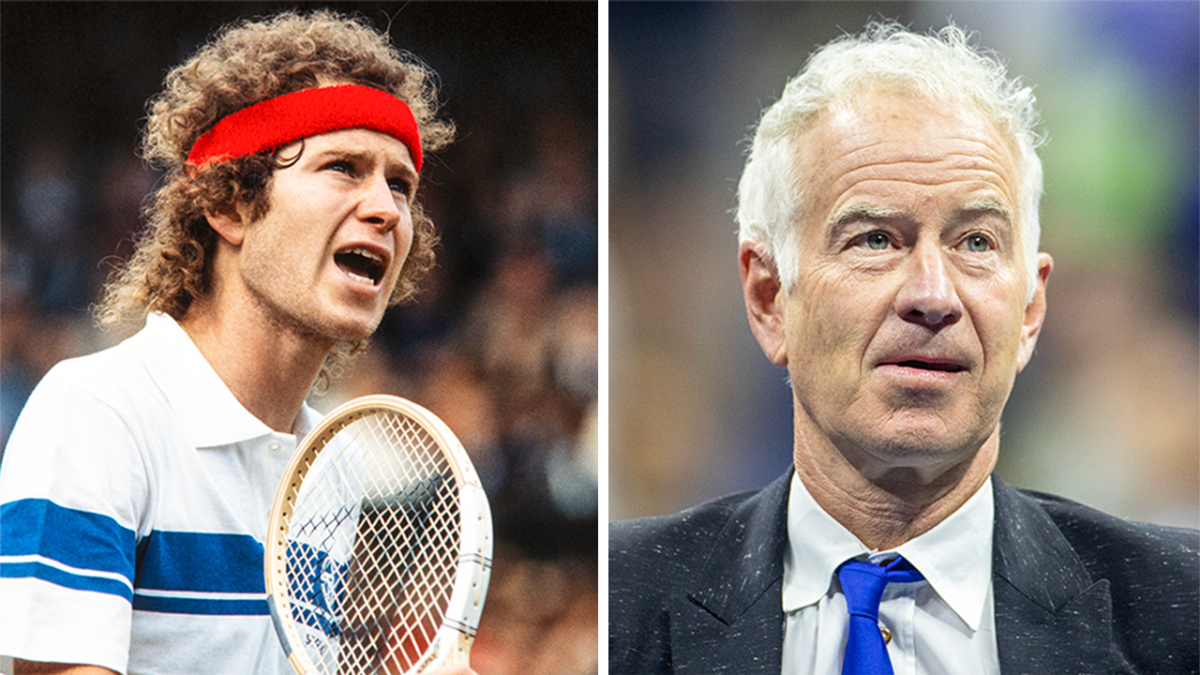

Towards the end of his self-titled documentary, John McEnroe wonders out loud what made him such a ticking timebomb.

“Why was I such a lunatic on the court? Thirty-seven psychologists and psychiatrists have never been able to figure it out,” he says.

HUGE: Djokovic’s staggering move amid Simona Halep doping furore

‘TOTAL MESS’: Ash Barty at centre of bizarre WTA controversy

“What are you? A stupid, f**king moron? I was crazed.

“I’m not at peace. I don’t even know what that feels like. Does that even exist?”

McEnroe is still searching for inner calm after 63 years, following one of the most tumultuous and explosive careers in the history of not only tennis, but sport.

This fascinating documentary – simply called McEnroe – begins by delving into the player’s childhood in Douglastown, New York, as he strolls the city streets in the middle of the night.

It’s where he and his father – John senior (not that you’re allowed to call him that to his face. He is John and his son is “John junior”) – have constant “high decibel conversations”.

The kid is a perfectionist – he still agonises over an A-minus in an early report card – and there is little affection or warmth from the man he most wants to impress, his father.

He channels all this rage, all this anger, into becoming the greatest tennis player in the world.

Maybe, he thinks, that will bring him and his dad, who has become his agent and is charging him by the hour, closer.

The opposite occurs, the chasm widening after McEnroe replaces his father with another manager capable of handling the most talked about sportsman on the planet.

“It was like I’d stabbed him in the back,” McEnroe reflects.

“Certain things were never resolved.”

John McEnroe’s tennis lessons from Borg and Connors

The documentary, by British filmmaker Barney Douglass, charts McEnroe’s difficult relationship with tennis officialdom, especially at stuffy Wimbledon, and his famous showdowns with Jimmy Connors and Bjorn Borg.

He idolised Borg and felt empty and robbed when the Swede called it quits at 26, just as their rivalry was reaching its peak.

Connors, McEnroe makes clear, had little time for him and the feeling soon became mutual.

“I said ‘Mr Connors, nice to me you’. He blew me off completely,” McEnroe says of their 1977 Wimbledon semi-final.

“Why is this guy such an arsehole? He won’t even acknowledge my existence.

“I was petrified. My legs were shaking and he’s treating me like absolute s**t.

“I did learn from him. You’ve got to be a bit of prick out there.”

It was a lesson McEnroe heeded, especially at Wimbledon.

“They were so proper. It was like an alien country to me,” he says.

“If I win it then I could really tell them to f**k themselves.

“If I ever win this f**king tournament, I’m never coming back.”

McEnroe did win Wimbledon, three times, the last victory in 1984 helping him maintain an incredible run of 170 weeks as world number one.

But he still felt so empty.

“I’m the greatest player that’s ever played. Why does it not feel that amazing?” McEnroe says of that period.

It took another decade, time away from tennis, a broken marriage to actress Tatum O’Neal, a dabble with drugs and, finally, the sudden death of his good friend and former pro Vitas Gerulaitis to deliver the biggest of wake-up calls.

“I was heading towards this potential cliff of some kind and hopefully I’d figure it out before I did anything stupid. It was a huge turning point of my life,” he says.

McEnroe is working hard in the fourth and fifth sets of life to make good on some of his mistakes.

Repairing fractured family relationships has been priority number one.

Son Kevin, recalling an argument over his dad’s commitment to his kids, reveals: “He (John) said ‘at least I’m consistent’. I said ‘consistently an arsehole’.”

McEnroe admits: “I’m not very empathetic. That’s my greatest flaw.

“I would dwell on tennis matches when I could have been a better dad.”

But by the end of McEnroe the documentary, we see the one-time angry man of tennis seemingly comfortable in his own skin as he enjoys a few laughs with his daughters at a café.

His wife – the singer Patty Smyth – remarks: “I married a bad boy who turned out to be a very good man.”

It’s McEnroe’s favourite line from the documentary.

Maybe he has found some form of peace after all.

-

McENROE IS AVAILABLE TO RENT AND OWN IN AUSTRALIA FROM 26TH OCTOBER. VISIT WWW.MCENROE-FILM.COM FOR MORE.

Click here to sign up to our newsletter for all the latest and breaking stories from Australia and around the world.